- Home

- Jeffery Deaver

Surprise Ending Page 2

Surprise Ending Read online

Page 2

“Of course,” Phan said, “we’ll keep your name out of it.”

“Appreciate that,” Seybold replied. But an idea floated into his thoughts. “Say it works out and he gets busted, this Federico. What do you think about me writing a true-crime book about it? I’d do it under a pseudonym.”

Visions of massive bestsellerdom—and a movie deal—pirouetted before his eyes.

“I don’t have any problem with that at all,” said Reynolds, who undoubtedly was already casting an actor for his role.

“When should we get together?”

“Tonight. The sooner we bring this guy down, the better for everybody.”

Alan Seybold was probably the only nominee for the ECWC Thriller of the Year award, in the history of the convention, who didn’t care a bit that he’d lost.

Now he could skip the after-party and meet with the cops and the CI at a motel ten blocks from the writers’ conference.

He ducked out after the last speech and made for the exit through the lobby. He noticed Maggie Daye, the fellow author, in the bar, sitting by herself. Hell, had he agreed to have a drink with her afterward? He didn’t think so. Still, he kept his head down and moved quickly outside into the cool April evening, the air redolent of the oily, fishy scent of harbor.

Enjoying the invigorating walk, Seybold passed a boarded-up tenement, next to a store selling bizarre-looking lamps. The cheapest price tag showed $600. Just beyond that was the battered façade of a bar that looked as if it had been here since Revolutionary times.

A few blocks farther down the busy commercial street, he came to the motel where the cops had taken a room—they used the place often to meet with CIs and witnesses, Phan had explained. A few minutes later Seybold was in the modest room. He doffed his coat and nodded greetings to Phan, Reynolds, and the third person present.

Stan Walker wasn’t what the author expected. He wasn’t a shifty, twitching little guy, but a calm, confident-looking young man, late twenties, with a Maryland drawl and ready smile. His eyes were shrewd, though, and suggested a quick mind. Which, the author imagined, was an important prerequisite in the confidential informant profession.

Walker pumped Seybold’s hand fiercely. “You’re my favorite author, sir. I have all your books. I mean, all of them.”

“Call me Alan, please,” he replied. The fan beamed.

“Any chance?” Walker produced two of his thrillers and Seybold signed them, adding “Best wishes” above his signature on the title page, which was a pretty lame sentiment, considering the absurdly dangerous position Walker was in.

The men sat around the coffee table of the suite and for two hours the officers and the CI fed Seybold a catalog of information about the gang boss. He took dozens of pages of notes. At one a.m. they called it a night, and the author snuck back to his hotel—more concerned about tipsy fans than Mafia hit men.

In his room he tossed his coat on the bed and dropped into the desk chair. With a scotch in hand, he read and reread his notes, absorbing the details about the man the police wanted behind bars so desperately. Andre Federico was the CEO of F&S Industries, Inc., a legitimate trucking and storage space company based in Baltimore. It was also a front for one of the biggest methamphetamine and opioid operations in the Northeast, grossing $490 million last year, it was estimated. He had affiliate relationships with the South Bay gangs in Boston and crews in Harlem and Philly and Washington, D.C.

Seybold had been curious about how Federico, the “new face” of organized crime, had chosen this path. The answer, Reynolds told him, wasn’t “the stuff of compelling fiction.” Federico’s father had owned a small landscaping company that had gone out of business, plunging the family into poverty. Federico’s only sibling, a younger brother, had died from pneumonia after the emergency room staff at a local hospital had failed to treat him promptly. Federico’s mother was never the same after that. His father repeatedly ran into trouble with loan sharks he borrowed money from in an effort to get a business going once more and keep it running. Several times he was badly beaten when he missed payments.

When Federico was in his midtwenties, the young man apparently decided, with simple and undeniable logic, that having money meant health and comfort. The other revelation, a bit thornier but equally logical, was that if those with money could beat up struggling businessmen like his father and let youngsters like his brother die, then it was morally fine to take that money away from them.

Young Andre had loved working for his father’s company, and so he began to take day jobs for landscapers in nice suburbs. He enjoyed the work—planting, raking, hoeing, trimming. But he enjoyed far more the money he made selling information about the clients’ security systems and gate and garage codes to professional thieves.

As the years passed, Federico decided that if you were going to break the law and risk going to prison, you should make sure the compensation was as high as it could be. Revenue from stealing jewelry, art, and silver paled in comparison to the gross income from selling drugs.

Which is the path he chose.

Simple and undeniable . . .

And a very successful path it was. Several times a week his crew met with buyers in the Baltimore/Washington area. A big buy going down tomorrow on the Baltimore waterfront was typical: Federico’s crew would deliver a shipment of opioids and walk away with a couple of million in cash from a gang out of Boston.

The mobster conducted all his illegal business from various remote locations, using pay phones exclusively. And even then he used the keypads to send codes, avoiding the risk of voiceprint identification. He sometimes met with associates in person but scanned them for listening devices and insisted they speak in euphemisms, never saying anything incriminating. His caution was so ingrained that, once, he walked away from a three-million-dollar deal, ordering the money be left behind, because of a “hunch” there might be some way to trace the cash to him.

The paranoia paid off, though, Seybold had to admit. Federico had no criminal record, which was almost unheard of for a mob boss at that level.

As for his personal life, Federico had been married for three decades. He was devoted to his children. Raine, 26, lived in Ellicott City, Maryland. His father had pulled strings to get him admitted to the best schools in the D.C. area. The son was smart, and he lived a high life as a broker for a securities firm on M Street, D.C. Kathy, Federico’s daughter, 19, was studying fashion at Tulane in New Orleans.

His wife and the children were completely isolated from the organized crime operation, per Federico’s orders, though Raine had shown an interest in the crew, according to the CI, Walker. The times he’d tried to hang out with them, his father had shooed him away, sometimes angrily. It was clear, though, he did this because he loved his boy deeply.

Seybold knew that personal faults were delightful weapons (ask the characters in his books, or his exes). But Federico seemed to have none. He wasn’t unfaithful, didn’t have a temper, wasn’t egotistical, was a moderate drinker, and was a supporter of good causes (from his church to cancer research to NPR). He never touched the products he made and sold. His hobby was gardening.

Seybold sat back and looked over his notes once more, waiting for inspiration. As a novelist, he often said there was no such thing as writer’s block; there was idea block. If you thought about your plot problem long enough, a solution would occur to you.

But nothing jumped out immediately.

Federico was smart and cautious, rich, a solid family man, few faults or vices . . .

Seybold rose and paced back and forth. He paused from time to time, hunching over the desk, and jotted notes. He crossed some out and jotted new ones. Some of those he crossed out too. Back to pacing. This was exactly how he wrote books: juggling ideas, like Steve Cameron’s partner dying at the hand of the villain, the love interest betraying him, the thief hiding the bomb in the banker’s study.

Sometimes the plot points came fast, sometimes he’d hit a brick wall . . . and, stiff

from all those hours of pacing through his San Francisco loft, he’d call the limo to come around and take him to his favorite bar or club in Nob Hill or South of Market.

Then he’d return home, to the chain gang of the word processor.

Breaking rocks to unearth those ideas.

He smiled to himself and ditched the embarrassing prisoner metaphor.

Okay, Mr. Federico, how do we bring you down?

And finally, an hour later, an idea blossomed, accompanied by a tap in his gut—so clear and sudden it seemed almost audible. Alan Seybold knew how to send Andre Federico to prison for the rest of his life.

He was amused to realize that he’d had the answer all along; in fact, he’d come up with it years ago.

“A book of mine,” Seybold said, “The Forgotten Sin.”

The time was nine a.m. and he was at the Maryland State Police’s Baltimore Organized Crime Task Force—specifically in Bradley Reynolds’s spacious corner office, which offered up one hell of a view of the harbor. Seybold, Reynolds, Louis Phan, and Stan Walker were clustered around the detective’s polished rosewood coffee table.

“A key element in the book is a father who sacrifices himself for his son. Now, Federico has no weaknesses we can exploit. But there is something we can use: his children. Rather than risk getting arrested, he’d walk away from everything—look at the time he abandoned that three million bucks. But abandon his son or daughter? Never.

“So we exploit that. And between the two, I’d pick his son. I imagine that Federico’s got a male, father-son thing going on. Think about his reaction to his father’s beatings. It affected him fundamentally. Oh, he loves his daughter, but he can’t wait to marry her off, I’ll bet. His son, though? See how he kept him close to home, the schools he picked? All local. So. Here’s my thought.” Seybold looked to Walker. “Can you find out the exact details of that drug sale today? On the waterfront?”

“Well, sure. But, with all respect, sir . . . Alan, what good does that do us? Federico never has connections with the shipments personally. He’s never close to either the money or the drugs.”

“We’re going to get him close. Using his son. Now who’re the players? What’s exactly going down?”

The officers looked to Walker, who said, “Federico’s crew, probably that asshole named Angel Ramos, is going to deliver two million bucks’ worth of opioids to a runner driving in from Massachusetts. It’ll go down at a warehouse near Fell’s Point. Pier 8.”

“When it does, you bust ’em,” Seybold said to Reynolds.

“Ramos’s not going to turn. Nobody dimes out Andre Federico.” This from Phan.

“No, that’s not what’s going to happen,” Seybold said. He was excited, sitting forward and gesturing with his hands. “We use Ramos’s phone to text his son and ask for a favor. What does Ramos drive?”

“Black Lexus.”

“Okay, you text Raine something like, ‘Do us a favor, kid. The Lexus’s at Pier 8. You’d be the man if you could drive it to your dad’s. We’ll take care of your wheels later . . . then you and me, we can hang out. We’d totally owe you. Keys under front seat.’ Oh, and I’d say MAN in all caps. Chest-bumping guy thing. Now, you can’t say you’re Ramos. That’d be entrapment, I’d guess.”

“It probably would,” Phan said.

“So don’t identify yourself. He’ll assume it’s Ramos.”

Reynolds laughed. “And everything you just said, in the text, could apply to us too. He’d be doing us a favor. We’ll take care of his car later. We’ll all hang out. And he’ll be the man because he’s helping us—put his father behind bars.”

Phan said, “Brilliant.”

Reynolds said, “He still might be suspicious.”

Seybold continued, “The kid’s dying to play gangster and now he’s going to take his first baby step. People’s suspicions vanish when it looks like they’re going to get what they want.”

“That a line from your book?” Reynolds asked.

“Yeah, as a matter of fact.”

Phan asked, “What if Ramos’s phone’s locked?”

Seybold had plotted this out too. “Right after the deal, Ramos’ll send one of those codes to Federico, right? To the pay phone?”

“To make sure it went okay, yeah.”

“The minute he disconnects, you’re on him—before the screen saver activates. Go to settings and disable the lock. Now, one other thing you have to do,” Seybold continued. “Get a warrant to suspend Federico’s phone service—mobile and landline—temporarily. Otherwise Raine might call daddy and ruin everything.”

Now it was Reynolds who had some problems. “Good up to a point. We get Ramos’s car on Federico’s property with two million and some drug residue in the trunk. But what’s the charge against Federico? A defense lawyer’ll have a field day tearing apart any case we try to put together. We can’t drive evidence up to a perp and force it on him.”

“Ah, that’s the brilliance,” Seybold offered, before deciding it wasn’t the most modest thing to say. “We don’t bust him. We bust the kid in front of him. Federico sees his son in cuffs. I guarantee he’ll confess to whatever charges you want if you let the boy go. Anything to save his son.”

Another line from the book.

The two officers and the CI shared a look. Reynolds finally spoke. “I’ll say one thing.”

“What’s that?” Seybold asked, concerned there was something he’d missed.

“I think we’re damn lucky you’re working for us and not for him.” The detective grinned big and shook Seybold’s hand. “Let’s put this thing together. We don’t have a lot of time.”

There was one problem with Seybold’s plan, though. In his view.

Reynolds wouldn’t let him come to the bust.

The author protested, “What about those ride-alongs? You see those on TV all the time.”

“That’s because it’s TV,” Phan had said. “All staged. This is real.”

Reynolds had been adamant. “It’s too dangerous. I told you, Ramos is a sadistic piece of shit. It could turn into a firefight. That happens, I don’t want to be distracted worrying about you.”

Seybold reluctantly agreed and wished them good luck. He left the officers and the CI at headquarters, where they would put together the details of the operation, coordinating with the tactical force. The deal was scheduled for four p.m. and it was now noon. They would have to race to make sure all the elements of the risky takedown were in place.

The author headed back to the hotel to have some lunch.

To answer some emails.

To dodge fans.

And to dress in camouflage—that is, black jeans, a black T-shirt, and a dark bomber jacket. A baseball cap too.

His acquiescence to Reynolds was purely for show. There was no way in hell he wasn’t going to the bust. He’d created the plot and he was going to be there when it went down. There was another reason for his presence too. He was going to record every minute of the operation in photographs, to use as illustrations in the pseudonymous book he planned to write about the case.

At three that afternoon, Seybold drove his rental car into a parking garage across the street from Pier 8. He continued to the top level and climbed out, then looked down thirty feet to the waterfront and adjacent areas. This neighborhood, though close to trendy Fell’s Point, was rough. There were, however, signs that it was changing. Among the decaying warehouses and trash and overturned Dumpsters and rotting piers were fancy pleasure craft tied up at secure docks. Construction was underway too—condos and retail space. He thought he saw the logo for a Bed Bath & Beyond.

Seybold glanced around him and noted no one present, then found a good vantage point between a couple of SUVs, where he’d have an unobstructed view of the warehouse beside Pier 8. He set up his big Sony A7, fitted with a telephoto lens, on a tripod.

For ten minutes he maintained his surveillance, crouching and ignoring the shooting pain from legs that spent more time in desk c

hairs than on treadmills. At one point he heard footsteps behind him and rose fast to see a fit, blond man in jeans and a navy-blue windbreaker about thirty feet away. He was looking toward Seybold. He wasn’t smiling and there was something unsettling about his stony gaze.

Did Ramos have someone checking out the area?

Hell, he hadn’t thought about that. And he should have; a careful author would have worked a character like this into the story—an associate of the paranoid mob boss, looking over the site of a deal. And Blondie had seen him with the camera. Maybe he’d think he was police and he’d figure there was a sting going on.

Oh, hell. I’m dead.

Or worse.

Pliers and soldering irons . . .

Seybold started to unscrew the camera from the tripod, planning to hightail it back to the car. But, looking about, he paused. Blondie was gone.

Scanning the area. Nothing. No sign of him.

I’m as paranoid as Federico.

Seybold returned to the vantage point and clicked the camera on, focused it carefully.

After a few minutes, a white van pulled up and a squat man in jeans and a gray sweatshirt got out of the passenger seat, studying the place. Seybold dubbed him “Boston.”

The camera clattered softly as it fired away, ten frames per second.

Boston said something to the driver, then pulled a white plastic bag from the passenger seat floor of the van. He started for the warehouse. The bag, which would contain the buy money, seemed heavy. Seybold recalled Walker saying it was two million.

All at once a half dozen cops appeared from the warehouse: While Reynolds subdued and cuffed Boston, Phan and several uniformed officers raced to the driver’s side of the van, and others to the rear. Simultaneously they ripped open the doors, then dragged the driver to the ground, cuffing him and pulling him inside the warehouse. Reynolds pulled on latex gloves and crouched, checking out the money. Then the detective rose and leaned close to Boston, threatening or negotiating or both.

A Maiden's Grave

A Maiden's Grave Trouble in Mind: The Collected Stories - 3

Trouble in Mind: The Collected Stories - 3 The October List

The October List The Deliveryman

The Deliveryman Garden of Beasts

Garden of Beasts Triple Threat

Triple Threat The Broken Window

The Broken Window The Steel Kiss

The Steel Kiss Twisted: The Collected Stories - 1

Twisted: The Collected Stories - 1 Solitude Creek

Solitude Creek Edge

Edge The Twelfth Card

The Twelfth Card The Bone Collector

The Bone Collector The Stone Monkey

The Stone Monkey The Sleeping Doll

The Sleeping Doll The Vanished Man

The Vanished Man The Kill Room

The Kill Room The Burial Hour

The Burial Hour An Acceptable Sacrifice

An Acceptable Sacrifice The Coffin Dancer

The Coffin Dancer The Lesson of Her Death

The Lesson of Her Death The Empty Chair

The Empty Chair The Burning Wire

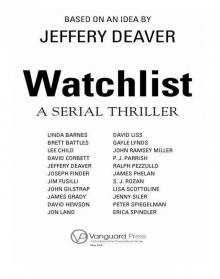

The Burning Wire Watchlist

Watchlist Captivated

Captivated The Cold Moon

The Cold Moon Speaking in Tongues

Speaking in Tongues Buried (Hush collection)

Buried (Hush collection) A Textbook Case

A Textbook Case The Victims' Club

The Victims' Club Nothing Good Happens After Midnight: A Suspense Magazine Anthology

Nothing Good Happens After Midnight: A Suspense Magazine Anthology The Bodies Left Behind

The Bodies Left Behind Turning Point

Turning Point Hard News

Hard News The Blue Nowhere

The Blue Nowhere The Second Hostage

The Second Hostage The Never Game

The Never Game The Devil's Teardrop

The Devil's Teardrop Death of a Blue Movie Star

Death of a Blue Movie Star The Skin Collector

The Skin Collector The Final Twist

The Final Twist Surprise Ending

Surprise Ending Twisted: The Collected Stories

Twisted: The Collected Stories Solitude Creek: Kathryn Dance Book 4

Solitude Creek: Kathryn Dance Book 4 Twisted: The Collected Short Stories of Jeffery Deaver

Twisted: The Collected Short Stories of Jeffery Deaver Rhymes With Prey

Rhymes With Prey Shallow Graves

Shallow Graves Bloody River Blues

Bloody River Blues Trouble in Mind: The Collected Stories, Volume 3

Trouble in Mind: The Collected Stories, Volume 3 Lincoln Rhyme 10 - The Kill Room

Lincoln Rhyme 10 - The Kill Room The Cutting Edge

The Cutting Edge Where the Evidence Lies

Where the Evidence Lies Hell's Kitchen

Hell's Kitchen Twisted

Twisted The Goodbye Man

The Goodbye Man The burning wire lr-9

The burning wire lr-9 The Blue Nowhere: A Novel

The Blue Nowhere: A Novel Roadside Crosses: A Kathryn Dance Novel

Roadside Crosses: A Kathryn Dance Novel The Debriefing

The Debriefing More Twisted: Collected Stories, Vol. II

More Twisted: Collected Stories, Vol. II The Kill Room lr-10

The Kill Room lr-10 A Dish Served Cold

A Dish Served Cold Bloody River Blues: A Location Scout Mystery

Bloody River Blues: A Location Scout Mystery The Bodies Left Behind: A Novel

The Bodies Left Behind: A Novel Where the Evidence Lies (A Mulholland / Strand Magazine Short)

Where the Evidence Lies (A Mulholland / Strand Magazine Short) A Textbook Case (lincoln rhyme)

A Textbook Case (lincoln rhyme) Copycat

Copycat The Chopin Manuscript: A Serial Thriller

The Chopin Manuscript: A Serial Thriller Carte Blanche

Carte Blanche The Sequel

The Sequel