- Home

- Jeffery Deaver

The Burning Wire Page 2

The Burning Wire Read online

Page 2

THE DRIVER EASED the M70 bus through traffic toward the stop on Fifty-seventh Street near where Tenth Avenue blended into Amsterdam. He was in a pretty good mood. The new bus was a kneeling model, which lowered to the sidewalk to make stepping aboard easier, and featured a handicapped ramp, great steering and, most important, a rump-friendly driver's seat.

Lord knew he needed that, spending eight hours a day in it.

No interest in subways, the Long Island Railroad or Metro North. No, he loved buses, despite the crazy traffic, the hostility, attitudes and anger. He liked how democratic it was to travel by bus; you saw everybody from lawyers to struggling musicians to delivery boys. Cabs were expensive and stank; subways didn't always go where you wanted to. And walking? Well, this was Manhattan. Great if you had the time but who did? Besides, he liked people and he liked the fact that he could nod or smile or say hello to every single person who got on his vehicle. New Yorkers weren't, like some people said, unfriendly at all. Just sometimes shy, insecure, cautious, preoccupied.

But often all it took was a grin, a nod, a single word . . . and they were your new friend.

And he was happy to be one.

If only for six or seven blocks.

The personal greeting also gave him a chance to spot the wackos, the drunks, the cluck-heads and tweakers and decide if he needed to hit the distress button.

This was, after all, Manhattan.

Today was beautiful, clear and cool. April. One of his favorite months. It was about 11:30 a.m. and the bus was crowded as people were heading east for lunch dates or errands on their hour off. Traffic was moving slowly as he nosed the huge vehicle closer to the stop, where four or five people stood beside a bus stop sign pole.

He was approaching the stop and happened to look past the people waiting to get on board, his eyes taking in the old brown building behind the stop. An early twentieth-century structure, it had several gridded windows but was always dark inside; he'd never seen anybody going in or out. A spooky place, like a prison. On the front was a flaking sign in white paint on a blue background.

ALGONQUIN CONSOLIDATED POWER

AND LIGHT COMPANY

SUBSTATION MH-10

PRIVATE PROPERTY

DANGER. HIGH VOLTAGE.

TRESPASS PROHIBITED.

He rarely paid attention to the place but today something had caught his eye, something, he believed, out of the ordinary. Dangling from the window, about ten feet off the ground, was a wire, about a half inch in diameter. It was covered with dark insulation up to the end. There, the plastic or rubber was stripped away, revealing silvery metal strands bolted to a fitting of some kind, a flat piece of brass. Damn big hunk of wire, he thought.

And just hanging out the window. Was that safe?

He braked the bus to a complete stop and hit the door release. The kneeling mechanism engaged and the big vehicle dipped toward the sidewalk, the bottom metal stair inches from the ground.

The driver turned his broad, ruddy face toward the door, which eased open with a satisfying hydraulic hiss. The folks began to climb on board. "Morning," the driver said cheerfully.

A woman in her eighties, clutching an old shabby Henri Bendel shopping bag, nodded back and, using a cane, staggered to the rear, ignoring the empty seats in the front reserved for the elderly and disabled.

How could you not just love New Yorkers?

Then sudden motion in the rearview mirror. Flashing yellow lights. A truck was speeding up behind him. Algonquin Consolidated. Three workers stepped out and stood in a close group, talking among themselves. They held boxes of tools and thick gloves and jackets. They didn't seem happy as they walked slowly toward the building, staring at it, heads close together as they debated something. One of those heads was shaking ominously.

Then the driver turned to the last passenger about to board, a young Latino clutching his MetroCard and pausing outside the bus. He was gazing at the substation. Frowning. The driver noticed his head was raised, as if he was sniffing the air.

An acrid scent. Something was burning. The smell reminded him of the time that an electric motor in the wife's washing machine had shorted out and the insulation burned. Nauseating. A wisp of smoke was coming from the doorway of the substation.

So that's what the Algonquin people were doing here.

That'd be a mess. The driver wondered if it would mean a power outage and the stoplights would go out. That'd be it for him. The crosstown trip, normally twenty minutes, would be hours. Well, in any event, he'd better clear the area for the fire department. He gestured the passenger on board. "Hey, mister, I gotta go. Come on. Get on--"

As the passenger, still frowning at the smell, turned around and stepped onto the bus, the driver heard what sounded like pops coming from inside the substation. Sharp, almost like gunshots. Then a flash of light like a dozen suns filled the entire sidewalk between the bus and the cable dangling from the window.

The passenger simply disappeared into a cloud of white fire.

The driver's vision collapsed to gray afterimages. The sound was like a ripping crackle and shotgun blast at the same time, stunning his ears. Though belted into his seat, his upper body was slammed backward against the side window.

Through numb ears, he heard the echoes of his passengers' screams.

Through half-blinded eyes, he saw flames.

As he began to pass out, the driver wondered if he himself might very well be the source of the fire.

Chapter 3

"I HAVE TO tell you. He got out of the airport. He was spotted an hour ago in downtown Mexico City."

"No," Lincoln Rhyme said with a sigh, closing his eyes briefly. "No . . ."

Amelia Sachs, sitting beside Rhyme's candy apple red Storm Arrow wheelchair, leaned forward and spoke into the black box of the speakerphone. "What happened?" She tugged at her long red hair and twined the strands into a severe ponytail.

"By the time we got the flight information from London, the plane had landed." The woman's voice blossomed crisply from the speakerphone. "Seems he hid on a supply truck, snuck out through a service entrance. I'll show you the security tape we got from the Mexican police. I've got a link. Hold on a minute." Her voice faded as she spoke to her associate, giving him instructions about the video.

The time was just past noon and Rhyme and Sachs were in the ground-floor parlor turned forensic laboratory of his town house on Central Park West, what had been a gothic Victorian structure in which had possibly resided--Rhyme liked to think--some very unquaint Victorians. Tough businessmen, dodgy politicians, high-class crooks. Maybe an incorruptible police commissioner who liked to bang heads. Rhyme had written a classic book on old-time crime in New York and had used his sources to try to track the genealogy of his building. But he could find no pedigree.

The woman they were speaking with was in a more modern structure, Rhyme had to assume, three thousand miles away: the Monterey office of the California Bureau of Investigation. CBI Agent Kathryn Dance had worked with Rhyme and Sachs several years ago, on a case involving the very man they were now closing in on. Richard Logan was, they believed, his real name. Though Lincoln Rhyme thought of him mostly by his nickname: the Watchmaker.

He was a professional criminal, one who planned his crimes with the precision he devoted to his hobby and passion--constructing timepieces. Rhyme and the killer had clashed several times; Rhyme had foiled one of his plans but failed to stop another. Still, Lincoln Rhyme considered the overall score a loss for himself since the Watchmaker wasn't in custody.

Rhyme leaned his head back in his wheelchair, picturing Logan. He'd seen the man in person, up close. Body lean, hair a dark boyish mop, eyes gently amused at being questioned by the police, never revealing a clue to the mass murder he was planning. His serenity seemed to be innate, and it was what Rhyme found to be perhaps the most disturbing quality of the man. Emotion breeds mistake and carelessness, and no one could ever accuse Richard Logan of being emotional.

He could be hired for lar

ceny or illegal arms or any other scheme that needed elaborate planning and ruthless execution, but was generally hired for murder--killing witnesses or whistle-blowers or political or corporate figures. Recent intelligence revealed he'd taken a murder assignment in Mexico somewhere. Rhyme had called Dance, who had many contacts south of the border--and who had herself nearly been killed by the Watchmaker's associate a few years earlier. Given that connection, Dance was representing the Americans in the operation to arrest and extradite him, working with a senior investigator of the Ministerial Federal Police, a young, hardworking officer named Arturo Diaz.

Early that morning they'd learned the Watchmaker would be landing in Mexico City. Dance had called Diaz, who scrambled to put extra officers in place to intercept Logan. But, from Dance's latest communication, they hadn't been in time.

"You ready for the video?" Dance asked.

"Go ahead." Rhyme shifted one of his few working fingers--the index finger of his right hand--and moved the electric wheelchair closer to the screen. He was a C4 quadriplegic, largely paralyzed from the shoulders down.

On one of the several flat-screen monitors in the lab came a grainy night-vision image of an airport. Trash and discarded cartons, cans and drums littered the ground on both sides of the fence in the foreground. A private cargo jet taxied into view and just as it stopped a rear hatch opened and a man dropped out.

"That's him," Dance said softly.

"I can't see clearly," Rhyme said.

"It's definitely Logan," Dance reassured. "They got a partial print--you'll see in a minute."

The man stretched and then oriented himself. He slung a bag over his shoulder and, crouching, ran toward and hid behind a shed. A few minutes later a worker came by, carrying a package the size of two shoe boxes. Logan greeted him, swapped the box for a letter-size envelope. The worker looked around and walked away quickly. A maintenance truck pulled up. Logan climbed into the back and hid under some tarps. The truck disappeared from view.

"The plane?" he asked.

"Continued on to South America on a corporate charter. The pilot and copilot claim they don't know anything about a stowaway. Of course they're lying. But we don't have jurisdiction to question them."

"And the worker?" Sachs asked.

"Federal police picked him up. He was just a minimum-wage airport employee. He claims somebody he didn't know told him he'd be paid a couple of hundred U.S. to deliver the box. The money was in the envelope. That's what they lifted the print from."

"What was in the package?" Rhyme asked.

"He says he doesn't know but he's lying too--I saw the interview video. Our DEA people're interrogating him. I wanted to try to tease some information out of him myself but it'll take too long for me to get the okay."

Rhyme and Sachs shared a look. The "teasing" reference was a bit of modesty on Dance's part. She was a kinesics expert--body language--and one of the top interrogators in the country. But the testy relationship between the sovereign states in question was such that a California cop would have plenty of paperwork to negotiate before she could slip into Mexico for a formal interrogation, whereas the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency already had a sanctioned presence there.

Rhyme asked, "Where was Logan spotted in the capital?"

"A business district. He was trailed to a hotel, but he wasn't staying there. It was for a meeting, Diaz's men think. By the time they'd set up surveillance he was gone. But all the law enforcement agencies and hotels have his picture now." Dance added that Diaz's boss, a very senior police official, would be taking over the investigation. "It's encouraging that they're serious about the case."

Yes, encouraging, Rhyme thought. But he felt frustrated too. To be on the verge of finding the prey and yet to have so little control over the case . . . He found himself breathing more quickly. He was considering the last time he and the Watchmaker had been up against each other; Logan had out-thought everybody. And easily killed the man he'd been hired to murder. Rhyme had had all the facts at hand to figure out what Logan was up to. Yet he'd misread the strategy completely.

"By the way," he heard Sachs ask Kathryn Dance, "how was that romantic weekend away?" This had to do, it seemed, with Dance's love interest. The single mother of two had been a widow for several years.

"We had a great time," the agent reported.

"Where did you go?"

Rhyme wondered why on earth Sachs was asking about Dance's social life. She ignored his impatient glance.

"Santa Barbara. Stopped at the Hearst Castle . . . Listen, I'm still waiting for you two to come out here. The children really want to meet you. Wes wrote a paper about forensics for school and mentioned you, Lincoln. His teacher used to live in New York and had read all about you."

"Yes, that'd be nice," Rhyme said, thinking exclusively about Mexico City.

Sachs smiled at the impatience in his voice and told Dance they had to go.

After disconnecting, she wiped some sweat from Rhyme's forehead--he hadn't been aware of the moisture--and they sat silent for a moment, looking out the window at the blur of a peregrine falcon sweeping into view. It veered up to its nest on Rhyme's second floor. Though not uncommon in major cities--plenty of fat, tasty pigeons for meals--these birds of prey usually nested higher. But for some reason several generations of the birds had called Rhyme's town house home. He liked their presence. They were smart, fascinating to watch and the perfect visitors, not demanding anything from him.

A male voice intruded, "Well, did you get him?"

"Who?" Rhyme snapped. "And how artful a verb is 'get'?"

Thom Reston, Lincoln Rhyme's caregiver, said, "The Watchmaker."

"No," grumbled Rhyme.

"But you're close, aren't you?" asked the trim man, wearing dark slacks, a businessman's starched yellow shirt and a floral tie.

"Oh, close," Rhyme muttered. "Close. That's very helpful. Next time you're being attacked by a mountain lion, Thom, how would you feel if the park ranger shot really close to it? As opposed to, oh, say, actually hitting it?"

"Aren't mountain lions endangered?" Thom asked, not even bothering with an ironic inflection. He was impervious to Rhyme's edge. He'd worked for the forensic detective for years, longer than many married couples had been together. And the aide was as seasoned as the toughest spouse.

"Ha. Very funny. Endangered."

Sachs walked around behind Rhyme's wheelchair, gripped his shoulders and began an impromptu massage. Sachs was tall and in better shape than most NYPD detectives her age and, though arthritis often plagued her knees and lower extremities, her arms and hands were strong and largely pain-free.

They wore their working clothes: Rhyme was in sweatpants, black, and a knit shirt of dark green. She had shed her navy blue jacket but was wearing matching slacks and a white cotton blouse, one button open at the collar, pearls present. Her Glock was high on her hip in a fast-draw polymer holster, and two magazines sat side by side in holsters of their own, along with a Taser.

Rhyme could feel the pulsing of her fingers; he had perfect sensation above where he'd sustained a nearly fatal spinal cord fracture some years ago, the fourth cervical vertebra. Although at one point he'd considered risky surgery to improve his condition, he'd opted for a different rehabilitative approach. Through an exhausting regimen of exercise and therapy he'd managed to regain some use of his fingers and hand. He could also use his left ring finger, which had for some reason remained intact after the subway beam broke his neck.

He enjoyed the fingers digging into his flesh. It was as if the small percentage of remaining sensation in his body was enhanced. He glanced down at his useless legs. He closed his eyes.

Thom now looked him over carefully. "You all right, Lincoln?"

"All right? Aside from the fact that the perp I've been searching for for years slipped out of our grasp and is now hiding out in the second-largest metropolitan area in this hemisphere, I'm just peachy."

"That's not what I'm talking about. You're not

looking too good."

"You're right. Actually I need some medicine."

"Medicine?"

"Whisky. I'd feel better with some whisky."

"No, you wouldn't."

"Well, why don't we try an experiment. Science. Cartesian. Rational. Who can argue with that? I know how I feel now. Then I'll have some whisky and I'll report back to you."

"No. It's too early," Thom said matter-of-factly.

"It's afternoon."

"By a few minutes."

"Goddamn it." Rhyme sounded gruff, as often, but in fact he was losing himself in Sachs's massage. A few strings of red hair had escaped from her ponytail and hung tickling against his cheek. He didn't move away. Since he'd apparently lost the single-malt battle, he was ignoring Thom, but the aide brought his attention around quickly by saying, "When you were on the phone, Lon called."

"He did? Why didn't you tell me?"

"You said you didn't want to be disturbed while you were talking with Kathryn."

"Well, tell me now."

"He'll call back. Something about a case. A problem."

"Really?" The Watchmaker case receded somewhat at this news. Rhyme understood that there was another source of his bad mood: boredom. He'd just finished analyzing the evidence for a complicated organized crime case and was facing several weeks with little to do. So he was buoyed by the thought of another job. Like Sachs's craving for speed, Rhyme needed problems, challenges, input. One of the difficulties with a severe disability that few people focus on is the absence of anything new. The same settings, the same people, the same activities . . . and the same platitudes, the same empty reassurances, the same reports from unemotional doctors.

What had saved his life after his injury--literally, since he'd been considering assisted suicide--were his tentative steps back into his prior passion: using science to solve crimes.

You could never be bored when you confronted mystery.

Thom persisted, "Are you sure you're up for it? You're looking a little pale."

"Haven't been to the beach lately, you know."

"All right. Just checking. Oh, and Arlen Kopeski is coming by later. When do you want to see him?"

The name sounded familiar but it left a vaguely troubling flavor in his mouth. "Who?"

"He's with that disability rights group. It's about that award you're being given."

A Maiden's Grave

A Maiden's Grave Trouble in Mind: The Collected Stories - 3

Trouble in Mind: The Collected Stories - 3 The October List

The October List The Deliveryman

The Deliveryman Garden of Beasts

Garden of Beasts Triple Threat

Triple Threat The Broken Window

The Broken Window The Steel Kiss

The Steel Kiss Twisted: The Collected Stories - 1

Twisted: The Collected Stories - 1 Solitude Creek

Solitude Creek Edge

Edge The Twelfth Card

The Twelfth Card The Bone Collector

The Bone Collector The Stone Monkey

The Stone Monkey The Sleeping Doll

The Sleeping Doll The Vanished Man

The Vanished Man The Kill Room

The Kill Room The Burial Hour

The Burial Hour An Acceptable Sacrifice

An Acceptable Sacrifice The Coffin Dancer

The Coffin Dancer The Lesson of Her Death

The Lesson of Her Death The Empty Chair

The Empty Chair The Burning Wire

The Burning Wire Watchlist

Watchlist Captivated

Captivated The Cold Moon

The Cold Moon Speaking in Tongues

Speaking in Tongues Buried (Hush collection)

Buried (Hush collection) A Textbook Case

A Textbook Case The Victims' Club

The Victims' Club Nothing Good Happens After Midnight: A Suspense Magazine Anthology

Nothing Good Happens After Midnight: A Suspense Magazine Anthology The Bodies Left Behind

The Bodies Left Behind Turning Point

Turning Point Hard News

Hard News The Blue Nowhere

The Blue Nowhere The Second Hostage

The Second Hostage The Never Game

The Never Game The Devil's Teardrop

The Devil's Teardrop Death of a Blue Movie Star

Death of a Blue Movie Star The Skin Collector

The Skin Collector The Final Twist

The Final Twist Surprise Ending

Surprise Ending Twisted: The Collected Stories

Twisted: The Collected Stories Solitude Creek: Kathryn Dance Book 4

Solitude Creek: Kathryn Dance Book 4 Twisted: The Collected Short Stories of Jeffery Deaver

Twisted: The Collected Short Stories of Jeffery Deaver Rhymes With Prey

Rhymes With Prey Shallow Graves

Shallow Graves Bloody River Blues

Bloody River Blues Trouble in Mind: The Collected Stories, Volume 3

Trouble in Mind: The Collected Stories, Volume 3 Lincoln Rhyme 10 - The Kill Room

Lincoln Rhyme 10 - The Kill Room The Cutting Edge

The Cutting Edge Where the Evidence Lies

Where the Evidence Lies Hell's Kitchen

Hell's Kitchen Twisted

Twisted The Goodbye Man

The Goodbye Man The burning wire lr-9

The burning wire lr-9 The Blue Nowhere: A Novel

The Blue Nowhere: A Novel Roadside Crosses: A Kathryn Dance Novel

Roadside Crosses: A Kathryn Dance Novel The Debriefing

The Debriefing More Twisted: Collected Stories, Vol. II

More Twisted: Collected Stories, Vol. II The Kill Room lr-10

The Kill Room lr-10 A Dish Served Cold

A Dish Served Cold Bloody River Blues: A Location Scout Mystery

Bloody River Blues: A Location Scout Mystery The Bodies Left Behind: A Novel

The Bodies Left Behind: A Novel Where the Evidence Lies (A Mulholland / Strand Magazine Short)

Where the Evidence Lies (A Mulholland / Strand Magazine Short) A Textbook Case (lincoln rhyme)

A Textbook Case (lincoln rhyme) Copycat

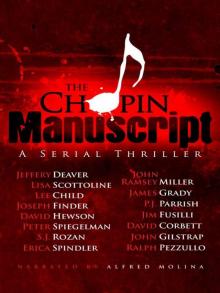

Copycat The Chopin Manuscript: A Serial Thriller

The Chopin Manuscript: A Serial Thriller Carte Blanche

Carte Blanche The Sequel

The Sequel