- Home

- Jeffery Deaver

The Never Game Page 18

The Never Game Read online

Page 18

37.

Jimmy Foyle, the cofounder of Knight Time, was in his mid-thirties.

Shaw recalled that he was also the chief game designer, the “gaming guru.” Whatever that meant.

The compact man had straight black hair in need of a trim. His face was boyish and chin dusted with faint stubble. His blue jeans were new, his black T-shirt ancient and the short-sleeved plaid overshirt, faded orange and black, was wrinkled. No corporate uniform for him, presumably because, as the creator of fifteen quadrillion planets, he could wear whatever the hell he wanted to.

Shaw decided the look was Zuckerberg-inspired, though more formal, owing to the overshirt.

Foyle was fidgety, not in an insecure way but in the manner of those who are intensely smart and whose fingers and limbs move in time to their spiraling minds. He had joined Knight and Shaw at the table in the workstation room, and the three were alone. Knight had cleared the room of the keyboarding employees by shouting, “Everyone, get out!”

Shaw sipped the coffee, which was a fine brew, yet the Costa Rican beans didn’t live up to their claim of overshadowing the Salvadoran.

Foyle was listening to Shaw’s explanation about the kidnappings, sitting forward at an acute angle. The man seemed shy and had made no pleasantries, offered no greetings; he had not shaken Shaw’s hand. A bit of Asperger’s, maybe. Or perhaps because software code looped through his thoughts constantly and the idea of social interaction emerged briefly, if at all. He wore no wedding ring or other jewelry. His loafers needed replacement. Shaw recalled the article about the game designer and assumed if you spent eighty hours a week in a dark room, it was because you enjoyed spending eighty hours a week in a dark room.

When Shaw finished, Foyle said, “Yes, I heard about the girl. And on the news this morning the other kidnapping. The journalists said it was likely the same man but they weren’t sure.” A Bostonian lilt to his voice; Shaw supposed he’d acquired his computer chops at MIT.

“We think probably.”

“There was nothing about The Whispering Man.”

“That’s my thought. I told the investigators but I’m not sure how seriously they took it.”

“Do the police have any hope of finding the new victim?” His language was stiff, formal in the way that Shaw supposed computer codes were formal.

“They didn’t have any leads as of an hour ago.”

“And your thought is that either he’s some troubled kid who’s taken the game to heart, like those boys a few years ago, or—alternatively—someone has hired him to pretend he’s a troubled kid to cover up something else.”

“That’s right.”

Knight asked, “What do you think, Jimmy?” Unlike his dictatorial attitude toward the other minions, with Foyle the CEO was deferential, almost obsequious.

Foyle drummed his fingers silently on his thigh while his eyes darted about. “Masquerading as a troubled gamer to cover up another reason for a kidnapping? I don’t know. It seems too complicated, too much work. There’d be too many chances to get found out.”

Shaw didn’t disagree.

“A troubled player, though, stepping over the line.” The man nodded thoughtfully. “Do you know Bartle’s categorization of video game players?”

Knight offered a gutsy laugh. “With all respect, he doesn’t know shit about games.”

Which wasn’t exactly true but Shaw remained silent.

Foyle went into academic mode. His eyes widened briefly—his first display of emotion, such as it was. “This is significant. There are four personality profiles of gamers, according to Bartle. One: Achievers. Their motivation is accumulating points in games and reaching preset goals. Two: Explorers. They want to spend time prowling through the unknown and discovering places and people and creatures that haven’t been seen before. Three: Socializers. They build networks and create communities.”

He paused for a moment. “Then, fourth: Killers. They come to games to compete, to win. That’s the sole purpose of gaming to them. Winning. Not necessarily to take lives; they enjoy race car and sports games too. First-person shooters are their favorites, though.”

Killers . . .

Foyle continued: “We spend a lot of time profiling who we’re creating games for. The profile of Killers is mostly male, fourteen to twenty-three, who play for at least three hours a day, often up to eight or ten. They frequently have troubled family lives, probably bullied at school, loners.

“But the key element of Killers is they need someone to compete against. And where do they find them? Online.”

Foyle fell silent and his face revealed a subtle glow of satisfaction.

Shaw didn’t understand why. “How does that profile help us?”

Both Knight and Foyle seemed surprised at the question. “Well,” the game designer said, “because it might just lead you straight to his front door.”

38.

Detective LaDonna Standish was saying, “Don’t mind admitting when I’m wrong.”

She was referring to her advice that Shaw leave Silicon Valley for home or to do some sightseeing.

They were in her office at the Task Force, only one half of which showed any signs of occupancy. The other hemisphere was completely vacant. There’d been no replacement found for Dan Wiley, who’d now be shuffling files to and from the various law enforcement agencies throughout Santa Clara County, a job that, to Shaw, would be a level of hell unto itself.

When Standish had stepped into the JMCTF reception area twenty minutes ago, Shaw had been amused to see her stages of reaction when he told her what he’d found: (1) confusion, (2) irritation and (3) after he’d shared what Jimmy Foyle had told him, interest.

Gratitude—reaction 3½?—had followed. She’d invited him to the office. Her desk was covered with documents and files. On the credenza pictures of friends and family, as well as several commendation plaques, were daunted by more files.

Jimmy Foyle’s idea was that if the suspect were a Killer he would be online almost constantly.

“His online presence defines him,” the designer had said. “Oh, he probably goes to school or a job, sleeps—though probably not much of that. He’ll be obsessed with the game and play it constantly.” Foyle had then sat forward with a slight smile. “But when do you know for certain the times he wasn’t playing?”

A brilliant question, Shaw had realized. And the answer: he wasn’t playing when he was kidnapping Sophie Mulliner and Henry Thompson and when he was shooting Kyle Butler.

He now told Standish, “The Whispering Man is a MORPG, a multiplayer online role-playing game. Players have to pay a monthly fee, which means Destiny, the publisher of the game, keeps credit cards on file.”

Standish’s thinking gesture was to touch an earring, a stud in the shape of a heart, an accessory in stark contrast to her outfit of cargo pants, black T and combat jacket. Not to mention the big-game Glock .45 on her hip.

“Foyle said we could use the credit card information to get a list of all the subscribers in the Silicon Valley area. Then we find out from the company who, among those, play obsessively but who weren’t online at the times of the kidnappings and Kyle’s murder.”

“That’ll work. I like it.”

“We need to talk to the head of Destiny, Marty Avon. Can you get a warrant?”

She chuckled. “Paper? Based on a video game? I’d be laughed out of the magistrate’s office.” She then turned her eyes his way. They were olive in color, and very dark, two tones deeper than her skin. Hard too. She added, “One thing I’m hearing, Mr. Shaw.”

“How about we do ‘Colter’ and ‘LaDonna.’”

A nod. “One thing I’m hearing: ‘we.’ The Task Force doesn’t deputize.”

“I’m helpful. You know it.”

“Rules, rules, rules.”

Shaw pursed his lips. “Upstate New York one time, I

was visiting my sister. A boy’d gone missing, lost in the woods near his house, it looked like. Five hundred acres. The police were desperate, blizzard coming on. They hired a local consultant to help.”

“Consultant?”

“A psychic.”

“For real?”

“I went to the sheriff too. I told him I had experience sign cutting—you know, tracking. I said I’d help them for free. The psychic was charging. They agreed.” He lifted his palms. “Don’t deputize me, LaDonna. Consultize me. Won’t cost the state a penny.”

A finger to the earlobe. “Out of harm’s way. No weapon.”

“No weapon,” he agreed, and could see, from the tightening of her lips, that she was aware he’d offered only half agreement.

They walked out of the Task Force building and into the parking lot, heading for her gray Altima. Standish asked, “How’d it turn out, that missing boy? Did she help?”

“Who?”

“The psychic.”

“How’d you know it was a woman?” Shaw asked.

“I’m psychic,” Standish said.

“She said she had a vision of the boy near a lake, making shelter under the trunk of a fallen walnut tree, four miles from the family house. A milk carton was nearby. And there was an old robin’s nest in a maple tree next to him.”

“Damn. That was one particular vision. Was she in the ballpark?”

“No. Took me ten minutes to find him. He was in the loft of the family’s garage. He’d been hiding there the whole time. He didn’t want to take his math test.”

39.

Your first name?” Standish asked Shaw. They were driving through Silicon Valley in her rickety car. Something was loose in the rear. “Never heard of it.”

“I’m one of three children,” Shaw told her. “Our father was a student of the Old West. I was named after the mountain man John Colter, with the Lewis and Clark Expedition. My kid sister’s Dorion, after Marie Aioe Dorion, one of the first mountain women in North America. She and her two kids survived for two months in the dead of winter in hostile territory—Marie Aioe, not my sister. My older brother, Russell, he was named after Osborne Russell, a frontiersman in Oregon.”

“They do this reward stuff too?”

“No.”

Though the apples didn’t fall far, at least in Dorion’s case. She worked for an emergency preparedness consulting company. Maybe in Russell’s too. But no one in the family knew where he was or what he was up to. Shaw had been trying to find him for years. Both hoping to and worried that he might succeed.

October 5, fifteen years ago . . .

Sometimes Shaw thought he should simply let it go.

He knew he wouldn’t.

Never abandon a task you know you must complete . . .

They were cruising along the 101, southbound, and had left the posh Neiman Marcus Silicon Valley behind, as well as the more modest yet tidy neighborhoods where the Quick Byte Café squatted and Frank Mulliner lived. Here, on either side of the freeway, badly in need of resurfacing, was hard urban turf, banger turf, city projects housing, abandoned buildings and overpasses dolled up with gang-sign graffiti.

According to GPS, the Destiny Entertainment Inc. offices were not far away. Shaw recalled Foyle telling him that The Whispering Man was the company’s main game. Maybe they hadn’t had any other big hits and the failures had kept the company on the wrong side of the tracks.

Shaw mentioned this to Standish as she pulled off the highway onto surface streets. “But it’s my wrong side of the tracks.”

He glanced her way.

“Home sweet home. EPA. East Palo Alto. Grew up here.”

“Sorry.”

She scoffed. “No offense taken. EPA . . . Doesn’t that confuse everybody? It’s really north of the other Palo Alto. Place so far on the wrong side you couldn’t even hear any train whistle. Your father liked his cowboys. Well, this was Tombstone back in the day. Highest murder rate in the country.”

“In Silicon Valley?”

“Yessir. It was mostly black then, thank you, because of the redlining and racial deed restrictions in SV.” She chuckled. “When I was growing up here, there was gunfire every night. We kids—I have three brothers—we’d hang out in Whiskey Gulch. Stanford was dry and didn’t allow any liquor within a mile of campus. And what was one mile and one block away? Yep, a strip mall in EPA, with package stores and bars galore. That’s where we’d play. Until Daddy came looking and dragged us home.

“’Course, the Gulch all got torn down and replaced with University Circle. Lord, there’s a Four Seasons Hotel there now! Just imagine that sacrilege, Colter. Last year, the murder rate was one—and that was a murder/suicide, some computer geek and his roommate. My daddy’d roll over in his grave.”

“You lose him recently?”

“Oh, years ago. Daddy, he didn’t benefit from the new and improved statistics. He was shot and killed. Right in front of our apartment.”

“That why you went into policing?”

“One hundred percent. High school, college in three years and into the academy at twenty-one, the minimum age. Then signed on with EPA police. I worked street while I got my master’s in criminal justice at night. Then moved to CID. Criminal investigation. Loved the job. But . . .” A wan smile.

“What happened?”

“Didn’t work out.” She added, “I didn’t blend. So I asked for a transfer to the Task Force.”

Shaw was confused. The population he was looking at was mostly black.

She noted his expression. “Oh, not that way. I’m talking ’bout my father. I didn’t explain. Yes, I went into policing because of him. But not because he was some poor innocent got gunned down in front of Momma and me. He was an OG.”

Shaw could imagine how her fellow cops would respond to working with the daughter of an original gangster whose crew might’ve shot at or even killed their friends.

“He was a captain in the Pulgas Avenue 13s. Warrant team from Santa Clara Narcotics came after him and it went south. After I was in, I snuck his file. My oh my, Daddy was a bad one. Drugs and guns, guns and drugs. Suspect in three hits. They couldn’t make two of the cases. The one where they had a good chance, the witness disappeared. Probably in the Bay off Ravenswood.”

A click of her tongue. “Wouldn’t you know it, my brothers and I would come home from school and, damn, if Momma was sick he’d have dinner ready and be reading us Harry Potter. He’d take us to the A’s games. Half my girlfriends didn’t have a father. Daddy was there. Until, yeah, he wasn’t.”

They continued in silence for five minutes, driving over dusty surface streets, wads of trash and soda and beer cans on the sidewalks and curbside. “It’s over there.” She nodded at a three-story building that seemed to be about fifty, sixty years old. This structure, along with several others nearby, wasn’t as shabby as the approach suggested they’d be. Destiny Entertainment’s headquarters was freshly painted, bright white. Shaw could see some smart storefront offices: graphic design and advertising agencies, a catering company, consulting.

Tombstone as reimagined by Silicon Valley developers.

They parked in the company’s lot. The other cars here were modest. Not the Teslas, Maseratis and Beemers of the nearby Google and Apple dimension. The lobby was small and decorated with what seemed to be artists’ renditions of the Whispering Man, ranging from stick drawings to professional-quality oils and acrylics. They’d have been done, he supposed, by subscribers. Shaw looked for the stenciled image that the kidnapper was fond of but didn’t see it. Standish seemed to be doing the same.

The receptionist told them Marty Avon would be free in a few minutes. A display caught Shaw’s eye and they walked to a waist-high table, six by six feet, that held a model of a suburban village. A sign overhead read WELCOME TO SILICONVILLE.

A placard explained

that the model was a mock-up of a proposed residential development that would be built on property in unincorporated Santa Clara and San Jose counties. Marty Avon had conceived of the idea in reaction to the “excruciatingly expensive” cost of finding a home in the area.

Shaw thought of Frank and Sophie Mulliner’s exodus to Gilroy, the Garlic Capital of the World. And the Walmart hoboes whom Henry Thompson was writing about in his blog.

Eyes on the sign, Standish said, “Have a couple open cases in the Task Force. Some of the big tech companies, they run their own employee buses from San Francisco or towns way south or east. They’ve been attacked on the road. People’re pissed, thinking it’s those companies that’re responsible for everything being so expensive. There’ve been injuries. I told them, ‘Take the damn name off the side of the bus.’ Which they did. Finally.” Standish added with a wry smile, “Wasn’t rocket science.”

Avon had created a consortium of local corporations, Shaw read, who would offer the reasonably priced housing to employees.

A generous gesture. Clever too: Shaw suspected that the investors were worried about a brain drain—coders moving to the Silicon Cornfields of Kansas or Silicon Forests in Colorado.

He wondered if because Destiny Entertainment wasn’t in the same stratosphere as Knight Time and the other big gaming studios, Avon had chosen to expand into a new field—one with a guaranteed stream of revenue: real estate.

The receptionist then said that Avon would see them. They showed IDs and were given badges and directed to the top floor. Once off the elevator they noted a sign: THE BIG KAHUNA THATAWAY →.

“Hmm.” From Standish.

As they proceeded thataway, they passed thirty workstations. The equipment was old, nothing approaching the slick gadgets at Knight Time Gaming’s booth; Shaw could only imagine what that company’s headquarters was like.

Standish knocked on the door on which a modest sign read B. KAHUNA.

“Come on in!”

A Maiden's Grave

A Maiden's Grave Trouble in Mind: The Collected Stories - 3

Trouble in Mind: The Collected Stories - 3 The October List

The October List The Deliveryman

The Deliveryman Garden of Beasts

Garden of Beasts Triple Threat

Triple Threat The Broken Window

The Broken Window The Steel Kiss

The Steel Kiss Twisted: The Collected Stories - 1

Twisted: The Collected Stories - 1 Solitude Creek

Solitude Creek Edge

Edge The Twelfth Card

The Twelfth Card The Bone Collector

The Bone Collector The Stone Monkey

The Stone Monkey The Sleeping Doll

The Sleeping Doll The Vanished Man

The Vanished Man The Kill Room

The Kill Room The Burial Hour

The Burial Hour An Acceptable Sacrifice

An Acceptable Sacrifice The Coffin Dancer

The Coffin Dancer The Lesson of Her Death

The Lesson of Her Death The Empty Chair

The Empty Chair The Burning Wire

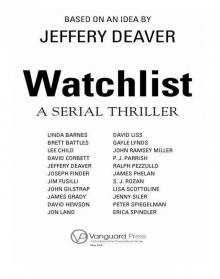

The Burning Wire Watchlist

Watchlist Captivated

Captivated The Cold Moon

The Cold Moon Speaking in Tongues

Speaking in Tongues Buried (Hush collection)

Buried (Hush collection) A Textbook Case

A Textbook Case The Victims' Club

The Victims' Club Nothing Good Happens After Midnight: A Suspense Magazine Anthology

Nothing Good Happens After Midnight: A Suspense Magazine Anthology The Bodies Left Behind

The Bodies Left Behind Turning Point

Turning Point Hard News

Hard News The Blue Nowhere

The Blue Nowhere The Second Hostage

The Second Hostage The Never Game

The Never Game The Devil's Teardrop

The Devil's Teardrop Death of a Blue Movie Star

Death of a Blue Movie Star The Skin Collector

The Skin Collector The Final Twist

The Final Twist Surprise Ending

Surprise Ending Twisted: The Collected Stories

Twisted: The Collected Stories Solitude Creek: Kathryn Dance Book 4

Solitude Creek: Kathryn Dance Book 4 Twisted: The Collected Short Stories of Jeffery Deaver

Twisted: The Collected Short Stories of Jeffery Deaver Rhymes With Prey

Rhymes With Prey Shallow Graves

Shallow Graves Bloody River Blues

Bloody River Blues Trouble in Mind: The Collected Stories, Volume 3

Trouble in Mind: The Collected Stories, Volume 3 Lincoln Rhyme 10 - The Kill Room

Lincoln Rhyme 10 - The Kill Room The Cutting Edge

The Cutting Edge Where the Evidence Lies

Where the Evidence Lies Hell's Kitchen

Hell's Kitchen Twisted

Twisted The Goodbye Man

The Goodbye Man The burning wire lr-9

The burning wire lr-9 The Blue Nowhere: A Novel

The Blue Nowhere: A Novel Roadside Crosses: A Kathryn Dance Novel

Roadside Crosses: A Kathryn Dance Novel The Debriefing

The Debriefing More Twisted: Collected Stories, Vol. II

More Twisted: Collected Stories, Vol. II The Kill Room lr-10

The Kill Room lr-10 A Dish Served Cold

A Dish Served Cold Bloody River Blues: A Location Scout Mystery

Bloody River Blues: A Location Scout Mystery The Bodies Left Behind: A Novel

The Bodies Left Behind: A Novel Where the Evidence Lies (A Mulholland / Strand Magazine Short)

Where the Evidence Lies (A Mulholland / Strand Magazine Short) A Textbook Case (lincoln rhyme)

A Textbook Case (lincoln rhyme) Copycat

Copycat The Chopin Manuscript: A Serial Thriller

The Chopin Manuscript: A Serial Thriller Carte Blanche

Carte Blanche The Sequel

The Sequel